The spinal column is the most common site for bone metastasis. Estimates indicate that at least 30 percent and as high as 70 percent of patients with cancer will experience spread of cancer to their spine.

Common primary cancers that spread to the spine are lung, breast and prostate. Lung cancer is the most common cancer to metastasize to the bone in men, and breast cancer is the most common in women. Other cancers that spread to the spine include multiple myeloma, lymphoma, melanoma and sarcoma, as well as cancers of the gastrointestinal tract, kidney and thyroid. Prompt diagnosis and identification of the primary malignancy is crucial to overall treatment. Numerous factors can affect outcome, including the nature of the primary cancer, the number of lesions, the presence of distant non-skeletal metastases and the presence and/or severity of spinal-cord compression.

Symptoms

Non-mechanical back pain, especially in the middle or lower back, is the most frequent symptom of both benign and malignant spinal tumors. This back pain is not specifically attributed to injury, stress or physical activity. However, the pain may increase with activity and is often worse at night. Pain may spread beyond the back to the hips, legs, feet or arms and may worsen over time — even when treated by conservative, nonsurgical methods that can often help alleviate back pain attributed to mechanical causes. Depending on the location and type of tumor, other signs and symptoms can develop, especially as a malignant tumor grows and compresses on the spinal cord, the nerve roots, blood vessels or bones of the spine. Impingement of the tumor on the spinal cord can be life-threatening in itself.

Additional symptoms can include the following:

Loss of sensation or muscle weakness in the legs, arms or chest

Difficulty walking, which may cause falls

Decreased sensitivity to pain, heat and cold

Loss of bowel or bladder function

Paralysis that may occur in varying degrees and in different parts of the body, depending on which nerves are compressed

Scoliosis or other spinal deformity resulting from a large, but benign tumor

Diagnosis

A thorough medical examination with emphasis on back pain and neurological deficits is the first step to diagnosing a spinal tumor. Radiological tests are required for an accurate and positive diagnosis.

X-ray: Application of radiation to produce a film or picture of a part of the body can show the structure of the vertebrae and the outline of the joints. X-rays of the spine are obtained to search for other potential causes of pain, i.e. tumors, infections, fractures, etc. X-rays are not very reliable in diagnosing tumors.

Computed tomography scan (CT or CAT scan): A diagnostic image created after a computer reads X-rays, a CT/CAT scan can show the shape and size of the spinal canal, its contents and the structures around it. It also is very good at visualizing bony structures.

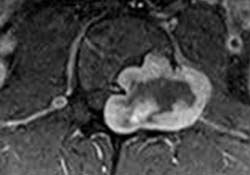

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): A diagnostic test that produces three-dimensional images of body structures using powerful magnets and computer technology. An MRI can show the spinal cord, nerve roots and surrounding areas, as well as enlargement, degeneration and tumors.

After radiological confirmation of the tumor, the only way to determine whether the tumor is benign or malignant is to examine a small tissue sample (extracted through a biopsy procedure) under a microscope. If the tumor is malignant, a biopsy also helps determine the cancer’s type, which subsequently determines treatment options.

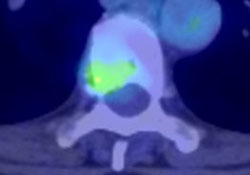

Staging classifies neoplasms (abnormal tissue) according to the extent of the tumor, assessing bony, soft tissue and spinal canal involvement. A doctor may order a whole body scan utilizing nuclear technology, as well as a CT scan of the lungs and abdomen for staging purposes. To confirm diagnosis, a doctor compares laboratory test results and findings from the aforementioned scans to the patient’s symptoms.

Treatment Decisions

Treatment decision-making is often multidisciplinary, incorporating the expertise of spinal surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists and other medical specialists. The selection of treatments including both surgical and non-surgical is therefore made keeping in mind the various aspects of the patient’s overall health and goals of care.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Nonsurgical treatment options include observation, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Tumors that are asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic and do not appear to be changing or progressing may be observed and monitored with regular MRIs. Some tumors respond well to chemotherapy and others to radiation therapy. However, there are specific types of metastatic tumors that are inherently radioresistant (i.e. gastrointestinal tract and kidney): in those cases, surgery may be the only viable treatment option.

Surgery

Indications for surgery vary depending on the type of tumor. In patients with metastatic tumors, treatment is primarily palliative, with the goal of restoring or preserving neurological function, stabilizing the spine and alleviating pain. Generally, surgery is only considered as an option for patients with metastases when they are expected to live 12 weeks or longer, and the tumor is resistant to radiation or chemotherapy. Indications for surgery include intractable pain, spinal-cord compression and the need for stabilization of impending pathological fractures.

For cases in which surgical resection is possible, preoperative embolization may be used to enable an easier resection. This procedure involves the insertion of a catheter or tube through an artery in the groin. The catheter is guided up through the blood vessels to the site of the tumor, where it delivers a glue-like liquid embolic agent that blocks the vessels that feed the tumor. When the blood vessels that feed the tumor are blocked off, bleeding can often be controlled better during surgery, helping to decrease surgical risks.

The posterior (back) approach allows for the identification of the dura and exposure of the nerve roots. Multiple levels can be decompressed, and multilevel segmental fixation can be performed. The anterior (front) approach is excellent for tumors in the front of the spine and effectively reconstructing defects caused by removal of the vertebral bodies. This approach also allows placement of short-segment fixation devices. Thoracic and lumbar spinal tumors that affect both the anterior and posterior vertebral columns can be a challenge to resect completely. Not infrequently, a posterior (back) approach followed by a separately staged anterior (front) approach has been utilized surgically to treat these complex lesions.

Recovery

The typical hospital stay after surgery to remove a spinal tumor ranges from 2 to 14 days, depending on the patient’s case. A required period of post-surgery physical rehabilitation may involve a stay in a rehabilitation hospital for a period of time. In other cases, physical therapy may take place at an outpatient facility or at the patient’s home. The total recovery time after surgery may be as short as three months or as long as one year, depending on the complexity of the surgery and the patient’s overall health.

Outcome

Outcome depends greatly on the age and overall health of the patient. In the case of metastatic tumors, the goal is almost always palliative, with treatment aimed at providing the patient with an improved quality of life and possibly prolonged life expectancy.

(aans.org)

Primary spinal tumors

Primary tumors originating from the spine are very complex and challenging entities totreat. Due to their rarity, a multicenter collaborative network is essential to shepherd thebest research and contribute to the dissemination of the best evidence possible. Overthe...

Spine tumors

Increasing number of people are suffering from a spine tumor. While primary tumors are rare conditions, metastatic lesions (a distant secondary tumor of a primary cancer) are more frequent due to the population aging and extended survival of cancer patients. These...